Imagine being able to invest in buzzy startups before they go public, or joining in on the high-stakes world of private equity and hedge funds. These opportunities are usually limited to the wealthy, but lawmakers are floating a new idea: if you can’t meet the money threshold, maybe you can prove your knowledge instead.

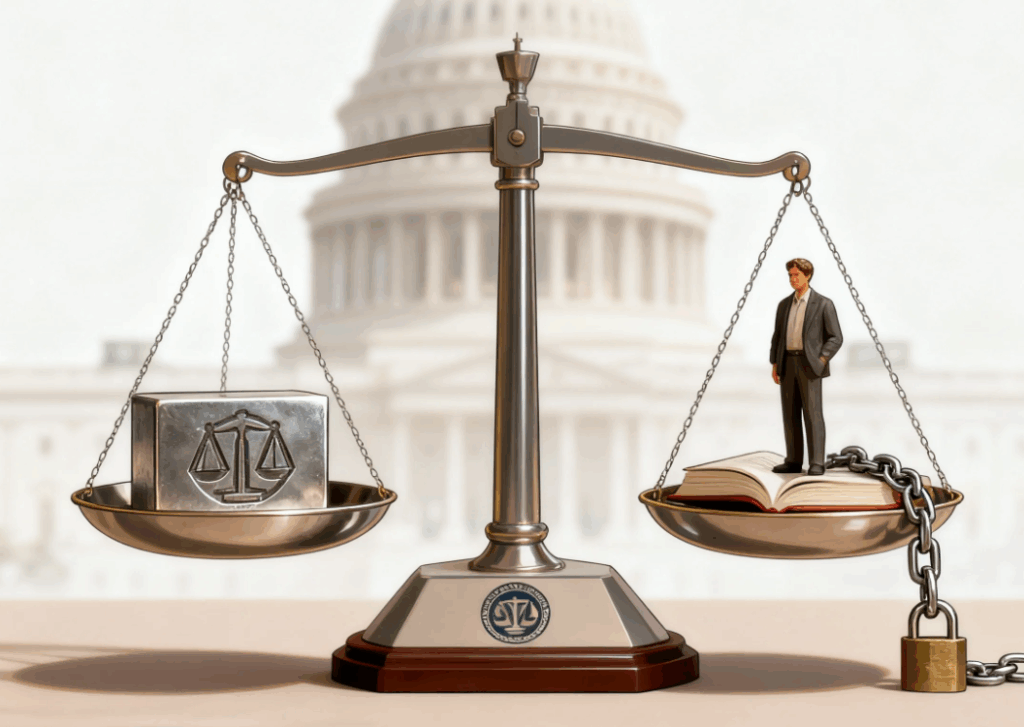

The U.S. House of Representatives recently backed a proposal for the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to design a knowledge exam that could grant access to “accredited investor” status. In theory, passing the test would show you understand the risks and complexities of private markets, opening the door to investments normally reserved for millionaires.

But here’s the challenge: most Americans struggle with even basic financial literacy. And experts warn that creating a fair and effective test won’t be easy.

What It Means to Be an Accredited Investor

Right now, accreditation is mostly about wealth. To qualify, you need at least $200,000 in annual income (or $300,000 as a couple), or $1 million in net worth excluding your primary home. Those thresholds haven’t budged since the 1980s, even as inflation and rising incomes have expanded the pool of qualifying households.

There’s also a backdoor for licensed professionals: passing Series 7, 65, or 82 exams automatically qualifies you. But these are exams for financial advisors and brokers, not everyday investors.

The proposed new route would let knowledge—not just net worth—be the ticket in. The question is: what exactly should be tested?

Designing the Exam: Easier Said Than Done

Experts say a meaningful test would have to go beyond definitions and jargon. It would need to cover:

- The risks of private assets, from limited liquidity to opaque disclosures.

- The reality that valuations can be subjective and horizons stretch over many years.

- How to fit alternative investments into a diversified portfolio.

“Essentially, the test would need to assess whether this person has the knowledge to manage investments without regulatory protections to lean on,” said Yanely Espinal, director of educational outreach at Next Gen Personal Finance.

That’s not simple. Even seasoned investors can get tripped up by hype. “We’ve been blessed with bull markets and high growth recently, but these things can go down and potentially default,” warned Chelsea Ransom-Cooper, CFP and chief financial planning officer at Zenith Wealth Partners.

Why It Matters

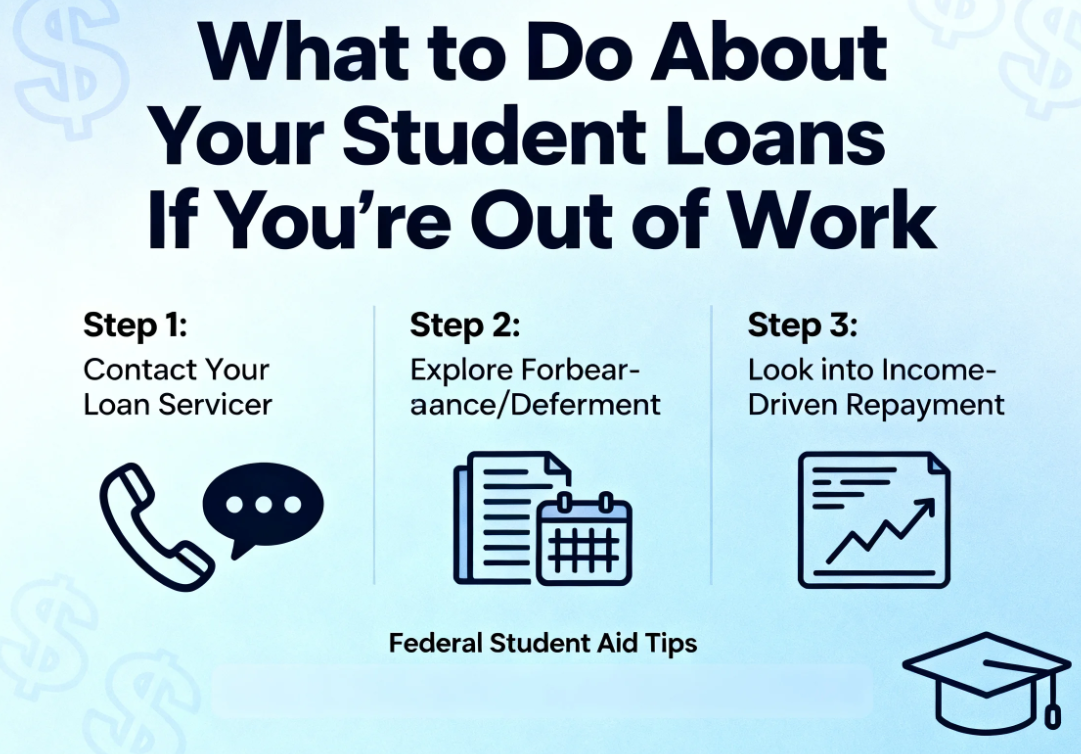

The stakes are real. Private-market deals often require large minimum investments—sometimes six figures. Losing just $20,000, for example, would wipe out nearly a quarter of the median U.S. household’s annual income ($80,610), Espinal pointed out.

Yet the rules don’t always line up logically. Crypto, considered just as risky as private equity, has no accreditation barrier. “You cannot invest in a real company that happens to be private, but you can invest in something equally risky, crypto,” said SEC advisory committee member James Andrus.

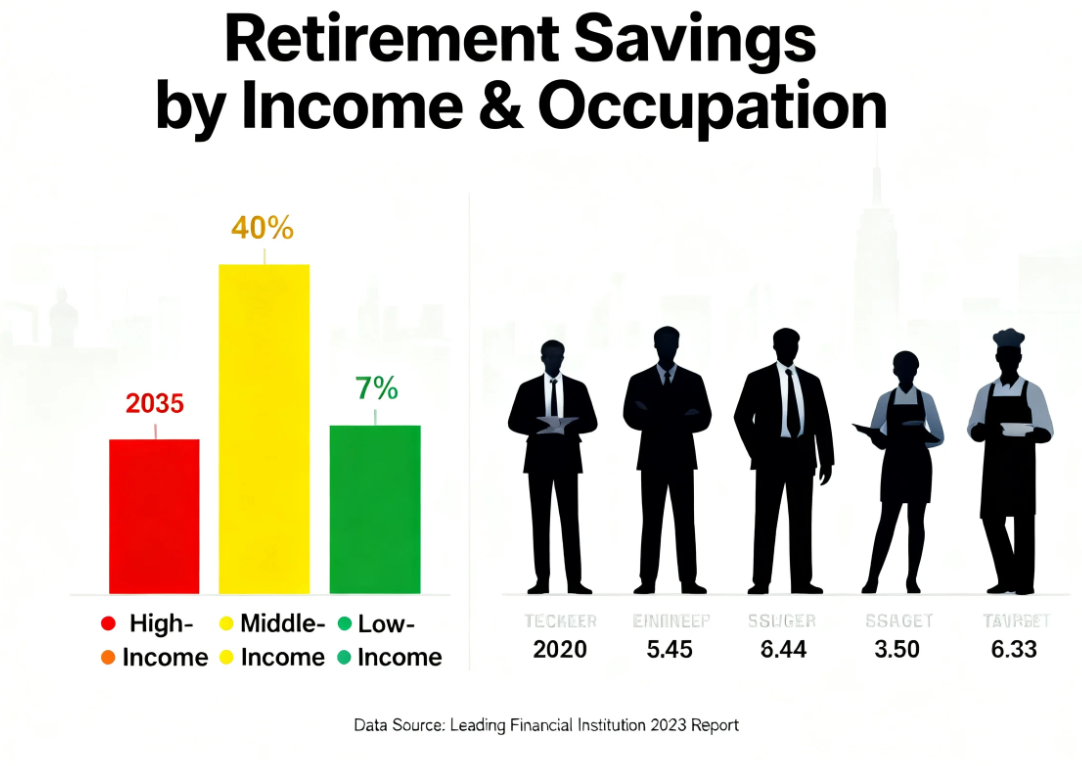

Americans Flunk Basic Finance Tests

If the SEC rolls out a knowledge exam, expect it to be a hurdle. Just look at existing data: the FINRA Investor Education Foundation runs a seven-question financial literacy quiz. Out of more than 25,000 U.S. adults surveyed in 2024, only 4% got all seven right. Less than half got even four correct.

Something as basic as “What happens to bond prices when interest rates rise?” stumped most respondents—42% said they didn’t know, and another 33% answered incorrectly. (The answer: prices fall.)

Even Wealthy Investors Could Use a Test

The irony is that plenty of accredited investors already lack true understanding. “A lot of people with a lot of money do these deals and have no freaking clue what they’re getting into,” said Rich Diemer, managing director of CAV Angels, a nonprofit angel investing group tied to the University of Virginia.

Diemer’s group educates members on due diligence, market potential, and the ongoing commitment needed to support startups. “It’s not a one-and-done,” he explained. “It’s about nursing an early-stage company along until VCs take over.”

For Diemer, a knowledge test could actually open doors—giving smart, younger investors without big bank accounts a fair shot at opportunities currently out of reach.

The Bottom Line

A knowledge exam for accredited investors could level the playing field, but it’s a double-edged sword. It might empower financially savvy individuals who aren’t wealthy, but it could also expose those who think they’re ready to risks they don’t fully grasp. Designing such a test is a puzzle regulators still haven’t solved—and whether it truly protects investors remains an open question.